- Journal List

- Sci Adv

- v.6(8); 2020 Feb

- PMC7030934

Vascular endothelium–targeted Sirt7 gene therapy rejuvenates blood vessels and extends life span in a Hutchinson-Gilford progeria model

Shimin Sun

1Anti-aging & Regenerative Medicine Research Institution, School of Life Sciences, Shandong University of Technology, Zibo 255049, China.

2National Engineering Research Center for Biotechnology (Shenzhen), Carson International Cancer Center, Medical Research Center, Shenzhen University Health Science Center, Shenzhen, China.

3Guangdong Key Laboratory of Genome Stability and Human Disease Prevention, Shenzhen University Health Science Center, Shenzhen, China.

Weifeng Qin

2National Engineering Research Center for Biotechnology (Shenzhen), Carson International Cancer Center, Medical Research Center, Shenzhen University Health Science Center, Shenzhen, China.

3Guangdong Key Laboratory of Genome Stability and Human Disease Prevention, Shenzhen University Health Science Center, Shenzhen, China.

Xiaolong Tang

2National Engineering Research Center for Biotechnology (Shenzhen), Carson International Cancer Center, Medical Research Center, Shenzhen University Health Science Center, Shenzhen, China.

3Guangdong Key Laboratory of Genome Stability and Human Disease Prevention, Shenzhen University Health Science Center, Shenzhen, China.

Yuan Meng

2National Engineering Research Center for Biotechnology (Shenzhen), Carson International Cancer Center, Medical Research Center, Shenzhen University Health Science Center, Shenzhen, China.

3Guangdong Key Laboratory of Genome Stability and Human Disease Prevention, Shenzhen University Health Science Center, Shenzhen, China.

Wenjing Hu

2National Engineering Research Center for Biotechnology (Shenzhen), Carson International Cancer Center, Medical Research Center, Shenzhen University Health Science Center, Shenzhen, China.

Shuju Zhang

2National Engineering Research Center for Biotechnology (Shenzhen), Carson International Cancer Center, Medical Research Center, Shenzhen University Health Science Center, Shenzhen, China.

3Guangdong Key Laboratory of Genome Stability and Human Disease Prevention, Shenzhen University Health Science Center, Shenzhen, China.

Minxian Qian

2National Engineering Research Center for Biotechnology (Shenzhen), Carson International Cancer Center, Medical Research Center, Shenzhen University Health Science Center, Shenzhen, China.

3Guangdong Key Laboratory of Genome Stability and Human Disease Prevention, Shenzhen University Health Science Center, Shenzhen, China.

4Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, School of Basic Medical Sciences, Shenzhen University Health Science Center, Shenzhen 518055, China.

Zuojun Liu

2National Engineering Research Center for Biotechnology (Shenzhen), Carson International Cancer Center, Medical Research Center, Shenzhen University Health Science Center, Shenzhen, China.

3Guangdong Key Laboratory of Genome Stability and Human Disease Prevention, Shenzhen University Health Science Center, Shenzhen, China.

4Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, School of Basic Medical Sciences, Shenzhen University Health Science Center, Shenzhen 518055, China.

Xinyue Cao

2National Engineering Research Center for Biotechnology (Shenzhen), Carson International Cancer Center, Medical Research Center, Shenzhen University Health Science Center, Shenzhen, China.

3Guangdong Key Laboratory of Genome Stability and Human Disease Prevention, Shenzhen University Health Science Center, Shenzhen, China.

4Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, School of Basic Medical Sciences, Shenzhen University Health Science Center, Shenzhen 518055, China.

Qiuxiang Pang

1Anti-aging & Regenerative Medicine Research Institution, School of Life Sciences, Shandong University of Technology, Zibo 255049, China.

Bosheng Zhao

1Anti-aging & Regenerative Medicine Research Institution, School of Life Sciences, Shandong University of Technology, Zibo 255049, China.

Zimei Wang

3Guangdong Key Laboratory of Genome Stability and Human Disease Prevention, Shenzhen University Health Science Center, Shenzhen, China.

4Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, School of Basic Medical Sciences, Shenzhen University Health Science Center, Shenzhen 518055, China.

Zhongjun Zhou

5School of Biological Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam, Hong Kong, China.

Baohua Liu

2National Engineering Research Center for Biotechnology (Shenzhen), Carson International Cancer Center, Medical Research Center, Shenzhen University Health Science Center, Shenzhen, China.

3Guangdong Key Laboratory of Genome Stability and Human Disease Prevention, Shenzhen University Health Science Center, Shenzhen, China.

4Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, School of Basic Medical Sciences, Shenzhen University Health Science Center, Shenzhen 518055, China.

6Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Regional Immunity and Diseases, School of Basic Medical Sciences, Shenzhen University Health Science Center, Shenzhen 518055, China.

Associated Data

- Supplementary Materials

- http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/6/8/eaay5556/DC1GUID: 104F0FCE-F34F-49A5-B590-536FE90DEA54Vascular endothelium–targeted Sirt7 gene therapy rejuvenates blood vesels and extends life span in a Hutchinson-Gilford progeria modelGUID: 104F0FCE-F34F-49A5-B590-536FE90DEA54

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/6/8/eaay5556/DC1

Fig. S1. Generation of Lmnaf/f mice and phenotypic analysis of LmnaG609G/G609G mice.

Fig. S2. Single-cell transcriptomic analysis of CD31+ MLECs.

Fig. S3. VE-specific progerin expression.

Fig. S4. Vasodilation analysis of LmnaG609G/+ mice.

Fig. S5. Expression of atherosclerosis- and osteoporosis-associated genes in MLEC transcriptomes.

Table S1. List of primer sequences.

Table S2. List of antibodies.

Abstract

Vascular dysfunction is a typical characteristic of aging, but its contributing roles to systemic aging and the therapeutic potential are lacking experimental evidence. Here, we generated a knock-in mouse model with the causative Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome (HGPS) LmnaG609G mutation, called progerin. The Lmnaf/f;TC mice with progerin expression induced by Tie2-Cre exhibit defective microvasculature and neovascularization, accelerated aging, and shortened life span. Single-cell transcriptomic analysis of murine lung endothelial cells revealed a substantial up-regulation of inflammatory response. Molecularly, progerin interacts and destabilizes deacylase Sirt7; ectopic expression of Sirt7 alleviates the inflammatory response caused by progerin in endothelial cells. Vascular endothelium–targeted Sirt7 gene therapy, driven by an ICAM2 promoter, improves neovascularization, ameliorates aging features, and extends life span in Lmnaf/f;TC mice. These data support endothelial dysfunction as a primary trigger of systemic aging and highlight gene therapy as a potential strategy for the clinical treatment of HGPS and age-related vascular dysfunction.

INTRODUCTION

Aging represents the largest risk factor for many age-related diseases, as exemplified by cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) (1). The blood vessel consists of the tunica intima [composed of endothelial cells (ECs)], the tunica media [composed of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs)], and the tunica adventitia (consisting of connective tissue) (2). The endothelium separates the vessel wall from blood flow and has an irreplaceable role in regulating vascular tone and homeostasis. Age-related functional decline in ECs and VSMCs is a main cause of CVDs (3). ECs secrete various vasodilators and vasoconstrictors that act on VSMCs and induce blood vessel contraction and relaxation (4). For instance, nitric oxide (NO) is synthesized from l-arginine by endothelial NO synthase (eNOS) and then released on VSMCs to induce blood vessel relaxation (5). When ECs become senescent or dysfunctional, vasoconstrictive, procoagulative, and proinflammatory cytokines are released; this effect reduces NO bioavailability and, in turn, increases vascular intimal permeability and EC migration (6). Despite advances in the understanding of mechanisms of endothelial dysfunction, it is unclear whether it directly triggers organismal aging.

Accumulating evidences suggest that the mechanisms underlying physiological aging are similar to those governing Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome (HGPS)—a premature aging syndrome in which affected patients typically succumb to CVDs (7). HGPS is predominantly caused by an a.c. 1824 C>T, p. G608G mutation in LMNA gene, which activates an alternate splicing event and generates a 50–amino acid truncated form of Lamin A, referred to as progerin (8). The murine LmnaG609G, which is equivalent to LMNAG608G in humans, causes aging phenotypes resembling HGPS (9). It has been shown that progerin targets SMCs and causes blood vessel calcification and atherosclerosis (10, 11). Recent work by two groups showed that SMC-specific progerin knock-in (KI) mice are healthy and have a normal life span but suffer from blood vessel calcification, atherosclerosis, and shortened life span when crossed to Apoe−/− mice (12, 13). In contrast to SMCs, the contributing roles of the vascular endothelium (VE) to systemic/organismal aging are still elusive. To address these issues, we generated a conditional progerin (LmnaG609G) KI model, i.e., Lmnaf/f mice. In combination with E2A-Cre and Tie2-Cre mice, in which the expression of Cre is ubiquitous including germ cells (14) or driven by the endothelial-specific Tie2 promoter (15), we aimed to investigate the roles of VE dysfunction to systemic aging and the targeting potential for the clinical treatment of HGPS.

RESULTS

Single-cell transcriptomic analysis reveals four predominant cell clusters in CD31+ MLECs

To study the mechanism of VE aging, we generated a mouse model of conditional progerin KI, in which the LmnaG609G mutation, equivalent to HGPS LMNAG608G, was flanked with loxP sites, i.e., Lmnaf/f mice (fig. S1A). The Lmnaf/f mice were crossed to E2A-Cre mice, in which the Cre recombinase is ubiquitously expressed including germ cells, to generate LmnaG609G/G609G and LmnaG609G/+ mice. Progerin was ubiquitously expressed in LmnaG609G/G609G and LmnaG609G/+ mice, which recapitulated many progeroid features found in HGPS, including growth retardation and shortened life span (fig. S1, B to D).

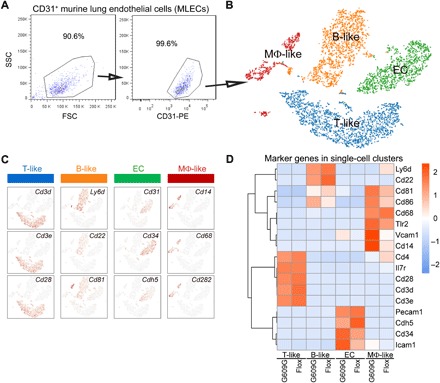

To understand primary alterations in the VE, we isolated CD31+ murine lung ECs (MLECs) (16) from three pairs of LmnaG609G/G609G (G609G) and Lmnaf/f (Flox) mice by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) (Fig. 1A) and performed 10× Genomics single-cell RNA sequencing. We recovered 6004 cells (4137 from G609G and 1867 from Flox mice) and used the k-means clustering algorithm to cluster the cells into four groups (Fig. 1B). As expected, one group exhibited high Cd31, Cd34, and Cdh5 expression and thus largely represented MLECs. The other three groups, copurified with CD31+ MLECs by FACS, showed relatively lower Cd31 expression at the mRNA level (>10-fold lower than MLECs) but high Cd45 expression (fig. S2). Further analysis revealed that these clusters most likely contained B lymphocytes (B-like) with high Cd22, Cd81, and Ly6d expression; T lymphocytes (T-like) with high Cd3d, Cd3e, and Cd28 expression; and macrophages (Mφ-like) with high Cd14, Cd68, and Cd282 expression (Fig. 1C). Most of the marker gene expression levels were comparable between G609G and Flox mice, except for Cd34 and Icam1, which were significantly elevated in G609G ECs, and Cd14 and Vcam1, which were increased in G609G Mφ-like cells (Fig. 1D). Of note, Icam1 and Vcam1 are among the most conserved markers of endothelial senescence and atherosclerosis (17). Thus, we established an Lmnaf/f conditional progerin KI mouse model and revealed a unique EC population for mechanistic study.

(A) Purity analysis of sorted CD31+ MLECs by FACS. SSC, side scatter; FSC, forward scatter; PE, phycoerythrin. (B) t-Distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) projection of CD31+ cells revealed four clusters: ECs (green), B lymphocytes (B-like; orange), T lymphocytes (T-like; blue), and macrophages (Mφ-like; red). (C) Marker gene expression in the four clusters: ECs (Cd31, Cd34, and Cdh5), B-like (Ly6d, Cd22, and Cd81), T-like (Cd3d, Cd3e, and Cd28), and Mφ-like (Cd14, Cd68, and Cd282). (D) Heatmap showing marker gene expression levels in LmnaG609G/G609G (G609G) and Lmnaf/f (Flox) mice.

Progeroid ECs develop a systemic inflammatory response

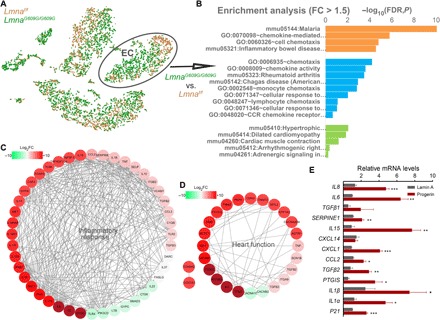

Of the four clusters of CD31+ MLECs, ECs and Mφ-like cells showed high levels of p21Cip1/Waf1 (fig. S2A), a typical senescence marker (18). This finding suggests that these cells are the main target of progerin in the context of aging. A previous study reported that Mφ-specific progerin, achieved by crossing Lmnaf/+ to Lyz-Cre mice, caused minimal aging phenotypes (12), implicating that Mφ might have only a minor role in organismal aging. We thus focused on ECs for further analysis. We recovered 899 and 445 ECs from E2A and Flox mice, respectively (Fig. 2A). Genes with >1.5-fold change in expression between these mice were chosen for Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analyses. We observed a significant enrichment in the pathways that regulate chemotaxis, immune responses in malaria and Chagas diseases, inflammatory bowel disease, and rheumatoid arthritis and pathways essential for cardiac function (Fig. 2, B to D). To confirm this observation and to exclude paracrine effects from other cell types, we overexpressed progerin in human umbilical vein ECs (HUVECs) and analyzed representative genes by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Most of the examined genes, e.g., IL6, IL8, IL15, CXCL1, IL1α, etc., were significantly up-regulated upon ectopic progerin overexpression (Fig. 2E). Together, these data suggest that progerin causes an inflammatory response in VE, which might lead to systemic aging.

(A) t-SNE projection of LmnaG609G/G609G (G609G; green) and Lmnaf/f (Flox; orange) CD31+ MLECs according to transcriptomic data. (B to D) GO and KEGG pathway enrichment of differentially expressed genes between G609G and Flox cells. LmnaG609G/G609G MLECs show enrichment in genes that regulate the inflammatory response (C) and genes related to heart dysfunction (D). FC, fold change; FDR, false discovery rate. (E) Quantitative PCR analysis of altered genes observed in (C) and (D) in HUVECs with ectopic expression of progerin or wild-type LMNA. Data represent means ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 (Student’s t test).

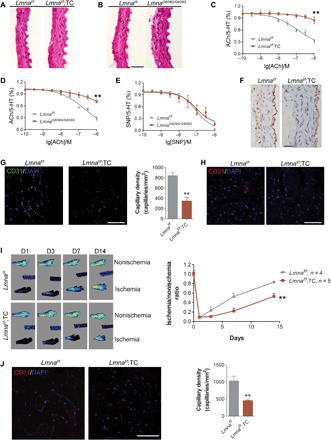

VE dysfunction causes vasodilation defects in progeria mice

To test whether the VE dysfunction has essential roles in systemic aging, we crossed Lmnaf/f mice to a Tie2-Cre line to generate Lmnaf/f;TC mice, in which the expression of Cre recombinase is driven by the promoter/enhancer of endothelial-specific Tie2 gene (15). Single-cell transcriptome analysis confirmed that Tie2 was mainly detected in ECs (fig. S2B). Consistently, progerin was observed in the VE of Lmnaf/f;TC, but not in that of Lmnaf/f control mice or other tissues (fig. S3). VE-specific progerin induced intima-media thickening in Lmnaf/f;TC mice, in a similar manner to total KI mice, i.e., LmnaG609G/G609G mice (Fig. 3, A and B). We performed functional analysis of the VE based on acetylcholine (ACh)–regulated vasodilation. ACh-induced thoracic aorta relaxation was significantly compromised in Lmnaf/f;TC mice (Fig. 3C). Similar defects were observed in LmnaG609G/G609G and LmnaG609G/+ mice (Fig. 3D and fig. S4), where progerin was expressed in both ECs and SMCs (12). To gain more evidence supporting VE-specific dysfunction, we examined thoracic aorta relaxation induced by sodium nitroprusside (SNP), which is an SMC-dependent vasodilator. Little difference was observed in thoracic aorta vasodilation in LmnaG609G/G609G and LmnaG609G/+ compared to Lmnaf/f control mice (Fig. 3E and fig. S4), supporting the notion that the VE dysfunction is a key contributor of vasodilation defects in progeria mice. As NO is the most potent vasodilator (19), we examined eNOS levels in the thoracic aorta of Lmnaf/f;TC and Lmnaf/f control mice. As expected, the level of eNOS was significantly reduced in Lmnaf/f;TC mice compared to Lmnaf/f control mice (Fig. 3F). Thus, the data confer a VE-specific dysfunction in progeria mice.

(A and B) Hematoxylin and eosin staining of thoracic aorta sections from (A) Lmnaf/f;TC and (B) LmnaG609G/G609G and Lmnaf/f control mice showing intima-media thickening. Scale bar, 20 μm. (C) ACh-induced thoracic aorta vasodilation in Lmnaf/f;TC and Lmnaf/f control mice. **P < 0.01. 5-HT, 5-hydroxytryptamine. (D) ACh-induced thoracic aorta vasodilation in LmnaG609G/G609G and control mice. **P < 0.01. (E) SNP-induced thoracic aorta vasodilation in LmnaG609G/G609G and control mice. (F) eNOS level in thoracic aorta sections from Lmnaf/f;TC and control mice. Scale bar, 20 μm. (G) Immunofluorescence staining (left) and quantification (right) of CD31+ gastrocnemius muscle in Lmnaf/f;TC and Lmnaf/f mice. Scale bar, 50 μm. DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. (H) CD31 immunofluorescence staining in Lmnaf/f;TC and Lmnaf/f liver. Scale bar, 50 μm. (I) Representative microcirculation images (left) and quantification of blood flow recovery (right) following hindlimb ischemia in Lmnaf/f;TC and Lmnaf/f mice. (J) Representative transverse sections and quantification of CD31+ gastrocnemius muscle 14 days after femoral artery ligation. Scale bar, 50 μm. All data represent means ± SEM. P values were calculated by Student’s t test. Photo credits: Shimin Sun, School of Life Sciences, Shandong University of Technology; Medical Research Center, Shenzhen University (A, B, F, H, and J); Weifeng Qin, Medical Research Center, Shenzhen University (G and I).

Defective neovascularization following ischemia in progeria mice

The reduced capillary density and neovascularization capacity are both characteristics of endothelial dysfunction (1). We examined the microvasculature in various tissues of Lmnaf/f;TC mice by immunofluorescence staining. We observed a significant loss in CD31+ ECs in Lmnaf/f;TC mice compared to controls (Fig. 3, G and H). We further examined ischemia-induced neovascularization ability in Lmnaf/f;TC mice following femoral artery ligation. Limb perfusion after ischemia was significantly blunted in Lmnaf/f;TC mice compared to controls (Fig. 3I). Histological analysis confirmed that the defect in blood flow recovery in Lmnaf/f;TC mice was a reflection of an impaired ability to form new blood vessels in the ischemic region (Fig. 3J). Together, Lmnaf/f;TC mice are characterized by a loss of ECs, a reduced capillary density, and defective neovascularization capacity.

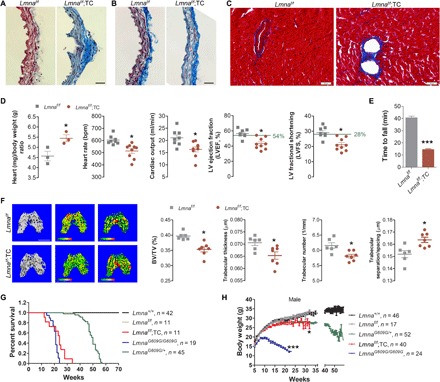

Endothelial dysfunction is a causal factor of systemic aging

The single-cell transcriptome implicates heart dysfunction in LmnaG609G/G609G mice (Fig. 2). A correlation with gene alterations associated with atherosclerosis and osteoporosis was obvious in LmnaG609G/G609G ECs (the Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man; https://omim.org) (fig. S5). We thus reasoned that endothelial-specific dysfunction might be enough to trigger systemic aging. Notably, atherosclerosis was prominent in Lmnaf/f;TC mice (aorta atheromatous plaque observed in all nine examined mice; Fig. 4A), as well as severe fibrosis in the arteries and hearts (Fig. 4, B and C); both are typical features of aging. Moreover, the heart/body weight ratio was significantly increased in Lmnaf/f;TC compared to Lmnaf/f control mice (Fig. 4D), indicating dilated cardiomyopathy (20). Echocardiography confirmed that heart rate, cardiac output, left ventricular ejection fraction, and fractional shortening were significantly reduced in 7- to 8-month-old Lmnaf/f;TC compared to Lmnaf/f control mice. The running endurance was largely compromised in Lmnaf/f;TC mice (Fig. 4E), which is likely a reflection of amyotrophy. Moreover, the micro–computed tomography (CT) identified a decrease in trabecular bone volume/tissue volume, trabecular thickness, and trabecular number but an increase in trabecular separation in Lmnaf/f;TC mice (Fig. 4F), indicative of osteoporosis, which is an important hallmark of systemic aging (21). The VE-specific dysfunction not only accelerated aging in various tissues/organs but also shortened the median life span of Lmnaf/f;TC mice (24 weeks) to a similar extent to LmnaG609G/G609G mice (21 weeks) (Fig. 4G). LmnaG609G/G609G mice suffered from body weight loss roughly from 8 weeks of age, while Lmnaf/f;TC mice only showed a slight drop in body weight (Fig. 4H), suggesting that body weight loss itself is a less likely primary causal factor to progeria compared to endothelial dysfunction. Together, these results implicate that endothelial dysfunction, at least in progeria, acts as a causal factor of systemic aging.

(A to C) Masson trichrome staining showing an atheromatous plaque in the aorta (A), SMC loss (B), and cardiac fibrosis (C) in Lmnaf/f;TC mice. Scale bar, 20 μm. (D) Heart weight and echocardiographic parameters, including heart rate, cardiac output, left ventricular (LV) ejection fraction (LVEF), and left ventricular ejection shortening (LVFS). *P < 0.05, Lmnaf/f;TC versus Lmnaf/f mice. (E) Decreased running endurance in Lmnaf/f;TC mice. ***P < 0.001. (F) Micro-CT analysis showing a decrease in trabecular bone volume/tissue volume (BV/TV), trabecular number, and trabecular thickness and an increase in trabecular separation in Lmnaf/f;TC mice. *P < 0.05, Lmnaf/f;TC versus Lmnaf/f mice. (G) Life span of LmnaG609G/G609G, LmnaG609G/+, Lmnaf/f;TC, and Lmnaf/f mice. (H) Body weight of male LmnaG609G/G609G, LmnaG609G/+, Lmnaf/f;TC, and Lmnaf/f mice. *P < 0.05, Lmnaf/f;TC versus Lmnaf/f mice; ***P < 0.001, LmnaG609G/G609G versus Lmnaf/f mice. All data represent means ± SEM. P values were calculated by Student’s t test, except that statistical comparison of the survival data was performed by log-rank test. Photo credits: Weifeng Qin, Medical Research Center, Shenzhen University (A and B); Shimin Sun, School of Life Sciences, Shandong University of Technology; Medical Research Center, Shenzhen University (C).

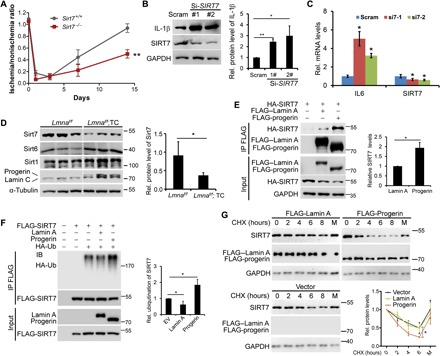

Accumulation of progerin destabilizes SIRT7

Loss of Sirt7, an NAD+ (nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide)–dependent deacylase, causes heart dysfunction with systemic inflammation and accelerates aging (22, 23). We noticed defective neovascularization in Sirt7 knockout mice (Fig. 5A). Knockdown of Sirt7 up-regulated the levels of interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and IL6 in HUVECs, as determined by Western blotting and real-time PCR (Fig. 5, B and C). Significantly, the protein level of Sirt7 was reduced almost 50% in Lmnaf/f;TC MLECs (Fig. 5D). By contrast, the levels of Sirt6 and Sirt1 were hardly decreased in Lmnaf/f;TC MLECs. Furthermore, co-immunoprecipitation revealed that Lamin A interacted with Sirt7, which was significantly enhanced in the case of progerin (Fig. 5E). FLAG-SIRT7 was polyubiquitinated, which was enhanced in the presence of progerin compared with Lamin A (Fig. 5F). Ectopic expression of progerin in human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 accelerated SIRT7 protein degradation, which was inhibited by MG132 (a proteasome inhibitor) (Fig. 5G). These data suggest that accumulation of progerin destabilizes Sirt7 by proteasomal pathway in progeria cells.

(A) Quantification of blood flow recovery following hindlimb ischemia in Sirt7−/− and Sirt7+/+ mice. (B) Left: Representative immunoblots showing indicated protein levels in HUVECs treated with si-SIRT7 or scramble (Scram). Right: Quantification of relative protein levels. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01, small interfering RNA (siRNA) versus Scram. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. (C) Real-time PCR analysis of the indicated gene expression in HUVECs treated with si-SIRT7 or Scram. *P < 0.05, siRNA versus Scram. (D) Left: Representative immunoblots showing indicated sirtuin protein levels in FACS-sorted MLECs. Right: Quantification of relative protein levels. *P < 0.05. Note that down-regulated Sirt7 but rather up-regulated Sirt6 and hardly changed SIRT1 in Lmnaf/f;TC MLECs. (E) Left: Co-immunoprecipitation (IP) experiments showing hemagglutinin (HA)–SIRT7 in anti–FLAG–Lamin A and anti–FLAG-progerin immunoprecipitates. Right: Quantification of relative protein levels. *P < 0.05. (F) Left: Representative immunoblots showing polyubiquitinated SIRT7, which was up-regulated in the presence of progerin but rather down-regulated in the presence of Lamin A. Right: Quantification of relative protein levels. *P < 0.05. (G) Representative immunoblots showing SIRT7 protein levels in the presence of Lamin A or progerin in HEK293 cells treated with cycloheximide (CHX) and/or MG132 (M). Quantification of relative SIRT7 protein levels was shown. *P < 0.05, progerin versus Lamin A. All data represent means ± SEM. P values were calculated by Student’s t test. Photo credit: Xiaolong Tang, Medical Research Center, Shenzhen University (B, D, E, F, and G).

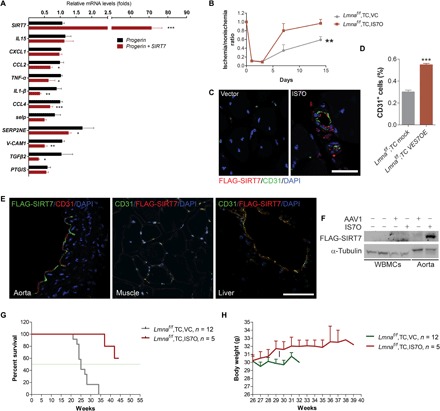

VE-specific expression of Sirt7 ameliorates aging features and extends life span

We reasoned that Sirt7 might underlie the VE dysfunction in progeria mice. To test this hypothesis, we first examined whether ectopic Sirt7 could rescue the exacerbated inflammatory response in HUVECs. As shown, overexpression of SIRT7 significantly down-regulated the expression of multiple inflammatory genes such as IL1β (Fig. 6A). To test the in vivo function of Sirt7 in defective neovascularization, we generated a recombinant AAV serotype 1 (rAAV1) cassette with Sirt7 gene expression driven by a synthetic ICAM2 promoter (IS7O), which ensures VE-specific expression (24, 25). As shown, on-site injection of IS7O at a dose of 1.25 × 1010 viral genome-containing particles (vg)/50 μl significantly improved blood vessel formation in Lmnaf/f;TC mice (Fig. 6B). The ectopic expression of Sirt7 and the increase in CD31-labeled ECs were evidenced by fluorescence confocal microscopy in ECs of regenerated blood vessels (Fig. 6, C and D).

(A) Real-time PCR analysis of genes that are aberrantly up-regulated in progerin-overexpressing HUVECs upon overexpression of SIRT7. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001. (B) Neovascularization assay in Lmnaf/f;TC mice with hindlimb ischemia, treated with or without IS7O particles. **P < 0.01. (C) Immunofluorescence microscopy analysis of FLAG-SIRT7 and CD31 expression in gastrocnemius muscle 14 days after femoral artery ligation. Scale bar, 25 μm. (D) Percent CD31+ ECs in Lmnaf/f;TC mice treated with or without IS7O particles. ***P < 0.001. (E) Representative immunofluorescence images of the liver, aorta, and muscle of Lmnaf/f;TC mice after IS7O therapy, showing CD31+ ECs with FLAG-SIRT7 expression. Scale bar, 50 μm. (F) Representative immunoblots showing expression of FLAG-SIRT7 in aorta and WBMCs. Note that FLAG-SIRT7 was merely detected in WBMCs. (G) Life span of IS7O-treated and untreated Lmnaf/f;TC and LmnaG609G/+ mice. (H) Body weight of IS7O-treated and untreated Lmnaf/f;TC and Lmnaf/f mice. All data represent means ± SEM. P values were calculated by Student’s t test, except that the statistical comparison of survival data was performed by log-rank test. Photo credits: Shimin Sun, School of Life Sciences, Shandong University of Technology; Medical Research Center, Shenzhen University (C and E); Xiaolong Tang, Medical Research Center, Shenzhen University (F).

We next asked whether IS7O could ameliorate premature aging and extend life span. To this end, the IS7O particles were injected via tail vein from 21 weeks of age, when progeria mice start to die. The injection was repeated every other week at a concentration of 5 × 1010 vg/200 μl per mouse. While all untreated mice died before 34 weeks of age, most IS7O-treated mice were still alive at the age of 44 weeks, when they were euthanized for histological analysis. The ectopic expression of FLAG-SIRT7 was observed in the ECs of liver, muscle, and aorta, but not in whole bone marrow cells (WBMCs), determined by fluorescence microscopy and/or Western blotting (Fig. 6, E and F). The median life span was extended by 76%—from 25 to >44 weeks (Fig. 6G). The age-related body weight loss was slightly rescued upon IS7O therapy in Lmnaf/f;TC mice (Fig. 6H). These data suggest that progerin-caused VE dysfunction and systemic aging are partially, if not entirely, attributable to Sirt7 decline.

DISCUSSION

Mounting evidence supports the idea that endothelial dysfunction is a conspicuous marker for vascular aging and CVDs (26–28). However, the fundamental question whether VE dysfunction causally triggers systemic aging remains. The heterogeneity of vascular cells and their close communication with the bloodstream render it difficult to understand the primary function of the VE. The murine LmnaG609G mutation, equivalent to the LMNAG608G found in humans with HGPS, causes premature aging phenotypes in various tissues and organs, thus providing an ideal model for studying aging mechanisms at both tissue and organismal levels. Data from the LmnaG609G model suggest that SMCs are the primary cause of vascular diseases, such as atherosclerosis (10, 11). A recent study showed that specific expression of LmnaG609G in SMCs causes atherosclerosis and shortens life span in atherosclerosis-prone Apoe−/− mice (12). We used Tie2-Cre line to generate the VE-specific LmnaG609G mouse model. Lmnaf/f;TC mice exhibited vascular dysfunction, accelerated aging, and a shortened life span to a similar extent to the whole-body LmnaG609G model. Tie2 expression was reported not only in ECs but also in hematopoietic lineages (29). Our single-cell transcriptomic data identified Tie2 transcripts mainly in MLECs instead of B-, T-, or Mφ-like cells. When a synthetic ICAM2 promoter was used to drive ectopic expression of FLAG-SIRT7 in the rescue experiments, ectopic FLAG-SIRT7 was successfully detected in ECs of the aorta, muscle, and liver but hardly detected in WBMCs. Therefore, Tie2-driven progerin expression combined with synthetic ICAM2-drivern SIRT7 rescue largely ensures the EC-specific contribution in systemic aging. Of note, although the number and function of hematopoietic stem cells decline in another progeria model, Zmpste24−/− mice (30), little effect was observed when healthy hematopoietic progenitor cells were transplanted to Zmpste24−/− mice in the context of systemic aging. Recently, Hamczyk et al. (12) found that knocking in the LmnaG609G allele in macrophages mediated by LysM-Cre merely affects aging and life span. Therefore, our data strongly suggest that, as the largest secretory organ (3), VE is pivotal in regulating systemic aging and longevity. In support of our findings, Foisner et al. (31) reported that VE-cadherin promoter-driven expression of progerin in a transgenic line causes cardiovascular abnormalities and shortens life span.

One limitation in the understanding of mechanisms of VE dysfunction is the vascular cell heterogeneity and the lack of appropriate in vitro system for ECs. Here, we took advantage of single-cell RNA sequencing technique to analyze the transcriptomes of MLECs. Unexpectedly, although >95% purity was achieved by FACS, MLECs isolated by CD31 immunofluorescence labeling turned out to be a mixture of cells, including ECs and T-, B-, and Mφ-like cells. Although enriched by FACS, these non-ECs expressed low level of CD31 mRNA, raising the possibility that cell surface proteins such as CD31 T-, B-, and Mφ-like cells might be obtained from neighbor ECs via intercellular protein transfer (32). Nevertheless, these findings suggest that one cannot just purify CD31+ cells and pool them together for mechanistic study, because one might arrive at a misleading conclusion. We compared the expression of genes that are associated with atherosclerosis, arthritis, heart failure, osteoporosis, or amyotrophy (the Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man; https://omim.org) between progeroid and control in all four clusters. An obvious alteration of these genes/pathways was observed mainly in ECs and Mφ-like cells (fig. S2). At the current stage, it is hard to separate cell-autonomous and paracrine effects among different cell populations. In the future, it would be worthwhile to do an analysis in Lmnaf/f;TC MLECs. The data will be useful to study the paracrine effect of ECs on other cell populations.

Since the identification of the causal link between LMNA G608G mutation and HGPS, numerous efforts have been put on the development of treatment for HGPS. Farnesyltransferase inhibitors (33), resveratrol, and N-acetyl cysteine (30) treatment alleviate premature aging features and extend life span in progeria murine models. Rapamycin (34) and metformin (35) incubation rescue senescence in HGPS cells. On the basis of these notions, patients with HGPS taking a farnesyltransferase inhibitor, lonafarnib, in a clinical trial showed significant improvement of health status, reduction of mortality rate, and a potential extension of life span (about 1 to 2 years) (36). Taking advantage of gene therapy and the dispensable role of Lamin A, morpholino oligos (9), and CRISPR-Cas9 designs (37, 38), which prevent Lamin A/progerin generation, can alleviate aging features and extend life span from 25 to 40% in progeria mice. However, considering the indispensable function of Lamin A in humans, these genome-modifying strategies need further experimentation before potential clinical application. Here, applying a different strategy, we showed that rAAV1-SIRT7 (IS7O), targeting dysfunctional VE, largely ameliorates progeroid features and almost doubles the median life span (from 25 to >44 weeks). To our best knowledge, this is the most marked rescue of progeria in a mouse model via gene therapy. Given that SIRT7 elicits deacylase activity to modulate cellular functions (22, 23), it is worthwhile to identify small molecules that specifically target SIRT7 activity for therapeutics in the future. Resveratrol is a potential activator of SIRT1, as well as SIRT7 (39), and has protective effects on vascular function and blood pressure (40). Further depicting the relationship of SIRT7 and resveratrol in the regulation of vascular function would help in seeking leading compounds of SIRT7 specific activators.

Collectively, we reveal VE dysfunction as a primary trigger of systemic aging and as a risk factor for age-related diseases such as atherosclerosis, heart failure, and osteoporosis. Drugs and molecules that target VE might serve as good candidates in the treatment of age-related diseases other than CVDs. The findings in SIRT7-based gene therapy implicate great clinical potentials for progeria as well as in antiaging applications.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Lmnaf/+ allele (LmnaG609G mutation flanked by two loxP sites) was generated by Cyagen Biosciences Inc., China. Briefly, the 5′ and 3′ homology arms were amplified from bacterial artificial chromosome clones RP23-21K15 and RP23-174J9, respectively. The G609G (GGC to GGT) mutation was introduced into exon 11 in the 3′ homology arm. C57BL/6 embryonic stem cells were used for gene targeting. To obtain ubiquitous expression of progerin (LmnaG609G/G609G), Lmnaf/f mice were bred with E2A-Cre mice. To obtain VE-specific expression of progerin, Lmnaf/f mice were bred with Tie2-cre mice. Mice were housed and handled in accordance with protocols approved by the Committee on the Use of Live Animals in Teaching and Research of Shenzhen University, China.

Hindlimb ischemia

Four-month-old male mice were anesthetized with 4% chloral hydrate (0.20 ml/20 g) by intraperitoneal injection. Hindlimb ischemia was performed by unilateral femoral artery ligation and excision, as previously described (41). In brief, the neurovascular pedicle was visualized under a light microscope following a 1-cm incision in the skin of the left hindlimb. Ligations were made in the left femoral artery proximal to the superficial epigastric artery branch and anterior to the saphenous artery. Then, the femoral artery and the attached branches between ligations were excised. The skin was closed using a 4-0 suture line, and erythromycin ointment was applied to prevent wound infection after surgery. Recovery of the blood flow was evaluated before and after surgery using a dynamic microcirculation imaging system (Teksqray, Shenzhen, China). Relative blood flow recovery is expressed as the ischemia-to-nonischemia ratio. At least three mice were included in each experimental group.

Cell culture

HEK293 cells and HUVECs were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection. HEK293 cells were cultured in Gibco Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Life Technologies, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum at 37°C, 5% CO2. HUVECs were cultured in Gibco M199 (Life Technologies, USA) supplemented with 15% fetal bovine serum, EC growth supplement (50 μg/ml), and heparin (100 μg/ml) at 37°C, 5% CO2. All cell lines used were authenticated by short tandem repeat profile analysis and were mycoplasma free.

RNA isolation and quantitative PCR analysis

Total RNA was extracted from cells or mouse tissues using TRIzol reagent RNAiso Plus (Takara, Japan) and transcribed into complementary DNA (cDNA) using 5× PrimeScript RT Master Mix (Takara, Japan), following the manufacturer’s instructions. The mRNA levels were determined by quantitative PCR with SYBR Premix Ex Taq II (Takara, Japan) detected on a CFX Connect Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad). All primer sequences are listed in table S1.

Protein extraction and Western blotting

For protein extraction, cells were suspended in SDS lysis buffer and boiled. Then, the lysate was centrifuged at 12,000g for 2 min, and the supernatant was collected. For Western blotting, protein samples were separated on SDS-polyacrylamide gels, transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore, USA), blocked with 5% nonfat milk, and incubated with the relevant antibodies. Images were acquired on a Bio-Rad system. All antibodies are listed in table S2.

Immunofluorescence staining

Frozen sections of aorta, skeletal muscle, and liver tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA), permeabilized with 0.3% Triton X-100, blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin and 1% goat serum, and then incubated with primary antibodies at room temperature for 2 hours or at 4°C overnight. After three washes with phosphate-buffered saline with Tween 20, the sections were incubated with secondary antibodies for 1 hour at room temperature and then stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole antifade mounting medium. Images were captured under a Zeiss LSM 880 confocal microscope. All antibodies are listed in table S2.

Masson trichrome staining

Paraffin-embedded sections of PFA-fixed tissues were dewaxed and hydrated. Staining was then performed using a Masson trichrome staining kit (Beyotime, China). In brief, the sections were dipped in Bouin buffer for 2 hours at 37°C and then successively stained with Celestine blue staining solution, hematoxylin staining solution, Ponceau S staining solution, and aniline blue solution for 3 min. After dehydrating with ethyl alcohol three times, the sections were mounted with Neutral Balsam Mounting Medium (BBI Life Science, China). Images were captured under a Zeiss LSM 880 confocal microscope.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting

Mice were euthanized by decapitation. The lungs were then collected, cut into small pieces, and then digested with collagenase I (200 U/ml) and neutral protease (0.565 mg/ml) for 1 hour at 37°C. The isolated cells were incubated with phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-CD31 antibody for 1 hour at 4°C and then 7-aminoactinomycin D (7-AAD) (1:100) for 5 min. CD31-positive and 7-AAD–negative cells were sorted on a flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, USA).

Myography

Four-month-old male mice were anesthetized with 4% chloral hydrate by intraperitoneal injection. Thoracic aortas were collected, rinsed in ice-cold Krebs solution, and cut into 2-mm-length rings. Each aorta ring was bathed in 5-ml oxygenated (95% O2 and 5% CO2) Krebs solution at 37°C for 30 min in a myograph chamber (620M, Danish Myo Technology). Each ring was stretched in a stepwise fashion to the optimal resting tension (thoracic aortas to ~9 mN) and equilibrated for 30 min. Then, 100 mM K+ Krebs solution was added to the chambers to elicit a reference contraction and then washed out with Krebs solution at 37°C until a baseline was achieved. Vasodilation induced by Ach or SNP (1 nM to 100 μM) was recorded in 5-hydroxytryptamine (2 μM) contracted rings. Data are represented as a percentage of force reduction and the peak of K+-induced contraction. At least three mice were included in each experimental group.

Echocardiography

Seven- to 8-month-old male mice were anesthetized by isoflurane gas inhalation and then subjected to transthoracic echocardiography (iU22, Philips). Parameters, including heart rate, cardiac output, left ventricular posterior wall dimension, left ventricular end-diastolic dimension, left ventricular end-systolic diameter, LV ejection fraction, and LV fractional shortening, were acquired. At least three mice were included in each experimental group.

Bone density analysis

Seven- to 8-month-old male mice were euthanized by decapitation. The thigh bone was fixed in 4% PFA at 4°C overnight. The relevant data were collected by micro-CT (Scanco Medical, μCT100). At least three mice were included in each experimental group.

Endurance running test

A Rota-Rod Treadmill (YLS-4C, Jinan Yiyan Scientific Research Company, China) was used to monitor fatigue resistance. Briefly, mice were placed on the rotating lane, and the speed of the rotations gradually increased to 40 rpm. When the mice were exhausted, they were safely dropped from the rotating lane, and the latency to fall was recorded. At least three mice were included in each experimental group.

10× Genomics single-cell RNA sequencing

CD31+ cells isolated from murine lung by FACS (>90% viability) were used for single-cell RNA sequencing. A sequence library was built according to the Chromium Single-Cell Instrument library protocol (42). Briefly, single-cell RNAs were barcoded and reverse-transcribed using the Chromium Single-Cell 3′ Reagent Kits v2 (10× Genomics) and then fragmented and amplified to generate cDNAs. The cDNAs were quantified using an Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 DNA Chip, and the library was sequenced using an Illumina Hiseq PE150 with ~10 to 30M raw data assigned for each cell. The reads were mapped to the mouse mm9 genome and analyzed using STAR: >90% reads mapped confidently to genomic regions and >50% mapped to exonic regions. Cell Ranger 2.1.0 was used to align reads, generate feature-barcode matrices, and perform clustering and gene expression analysis. Mean reads (>80,000) and 900 median genes per cell were obtained. The unique molecular identifier counts were used to quantify the gene expression levels, and the t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) algorithm was used for dimensionality reduction. The cell population was then clustered by k-means clustering (k = 4). The Log2FoldChange was the ratio of gene expression of one cluster to that of all other cells. The P value was calculated using the negative binomial test, and the false discovery rate was determined by the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure. GO and KEGG enrichment analyses were performed in DAVID version 6.8 (43).

Statistical analysis

A two-tailed Student’s t test was used to determine statistical significance, except that the statistical comparison of survival data was performed by log-rank test. All data are presented as the means ± SD or means ± SEM, as indicated, and a P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Tamanini (Shenzhen University and ETediting) for editing the manuscript before submission. Funding: This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (91849208, 81571374, 91439133, 81871114, 81601215, 81972602, and 81702909), the National Key R&D Program of China (2017YFA0503900), the Science and Technology Program of Guangdong Province (2014A030308011, 2017B030301016, and 2019B030301009), and the Shenzhen Municipal Commission of Science and Technology Innovation (JCYJ20160226191451487, KQJSCX20180328093403969, JCYJ20180507182044945, ZDSYS20190902093401689, and Discipline Construction Funding of Shenzhen 2016-1452). Author contributions: B.L. designed and supervised the project. S.S., W.Q., and X.T. conducted experiments with help from W.H., S.Z., M.Q., Z.L., X.C., Q.P., and B.Z. Y.M. performed bioinformatic analysis. Z.W. and Z.Z. provided resources. S.S., X.T., and B.L. wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the experimental results and reviewed the manuscript. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. The data of single-cell transcriptomics are available in the GEO database ({"type":"entrez-geo","attrs":{"text":"GSE138975","term_id":"138975"}}GSE138975). Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/6/8/eaay5556/DC1

Fig. S1. Generation of Lmnaf/f mice and phenotypic analysis of LmnaG609G/G609G mice.

Fig. S2. Single-cell transcriptomic analysis of CD31+ MLECs.

Fig. S3. VE-specific progerin expression.

Fig. S4. Vasodilation analysis of LmnaG609G/+ mice.

Fig. S5. Expression of atherosclerosis- and osteoporosis-associated genes in MLEC transcriptomes.

Table S1. List of primer sequences.

Table S2. List of antibodies.